In his post, Dennis Crouch laments the slow but steady loss of the original, solitary inventor that this portends. He starts the post with a reference to the way that (American?) culture emphasizes extroversion over introversion and then ties this to the increase in teamwork centered patents. While I believe the comment on culture increasingly valuing extroversion may have some merit to it, at least as limited to the United States, the link between this and multiple inventor patenting is not quite so easy to make.

What about the portion of US patents that are not invented in the United States? The proportion of this type of foreign application at the USPTO has been increasing over the last few decades, now taking up roughly 50% of total applications. They are therefore not just more and more important in terms of the overall make-up of granted US patents, but they are also more and more numerically significant in terms of calculating statistical trends. Do these types of applications also show an increase in multiple inventor inventions? My guess is that they do. While some may suggest that this is a result of some sort of overarching culture of modernity, this is unlikely given both the number of different cultural groups this would entail moving in the same direction and the ongoing dramatic differences between these groups in patenting styles. To boot, the vast majority of anthropological research into “modernity” has emphasized an increasing preoccupation with “the individual,” certainly not a trend that is easily fit with a parallel increase in multiple inventor patents. It could be that our preoccupation with the individual has caused us to ask this kind of question and therefore to “see” (and find significant) such a loss of the individual inventor. I don't, however, buy this response either. I believe the trend really is there. Since the United States has long celebrated a romantic view of a lone, genius (though perhaps a bit crazy) inventor it makes little sense to argue that we would only be recognizing this trend today.

So going back, then, to the argument that there may be a wide-ranging shift in cultures towards extroversion and therefore teamwork in patents, in my own fieldwork with Taiwanese patent and process engineers, I was told on several occasions of significant cultural differences in patenting practices (see also Libecap, 1989, "Contracting for Property Rights" on the lack of predicted movement toward some sort of global economic optimum in patent laws themselves). For instance, I was told that the Japanese style was to patent every little advance made in its own separate application. Americans, on the other hand, tended to wait until their smaller advances had added up to something slightly larger, a clear step forward rather than incremental improvement, before they would submit a new patent application. This particular difference in patenting behavior means that it makes little sense to compare the raw number of Japanese patents to the raw number of American patents. There are, of course, many further differences; this is only one example. Given such differences in styles of patenting, it would be quite surprising to see an overall move, based on a culture of modernity, toward multiple inventor patents.

This example, however, is also a good example of an odd trend among non-anthropologists. People (and I mean this in terms of Americans as well as Chinese and Taiwanese, at least) seem to have become more and more comfortable resorting to “culture” as an explanation of behavior. It is a quick, readily available, explanation that from an anthropologist's perspective often fails to really explain anything. Perhaps ironically, as we anthropologists are supposed to be culture's academic champions, what I am suggesting is that blaming culture has become too easy. Often, upon further analysis, cultural explanation turns out to have been masking other reasons for behavior. It would, for instance, make more sense to suggest that an overall change in patenting behavior at the USPTO is linked to policy at the USPTO rather than having its origins in simultaneous global cultural change. If this type of explanation based on American law, American legal precedent, or other patenting trends at the USPTO were insufficient, then it makes sense to look beyond this to overall trends. Going back to the example of Japanese versus American patenting differences, for instance, though these were relayed to me as cultural differences, they may not really be cultural at all. When the Company planned on patenting their Taiwanese inventions in Japan, for instance, they too would work on writing the patent in a way that fit with the larger Japanese patenting trend. For the US, several of these patents may be brought over together (see my earlier blog discussion of Nakamura's Japanese LED patent) into a single application (and then multiple divisionals as required by the patent examiner). Patenting style seems to me to be much more closely related to the rules and structures of that nation's patent office and courts of law1 rather than something more like “culture” per se.

So then where does this leave us? As a qualitative rather than quantitative researcher of patents, this is a question that I cannot answer definitively. However, what I can do is offer potential alternative solutions that quantitative researchers may not have thought of (or may not have thought significant enough). At the Company, one of the things that I noticed was that there were almost never patents submitted to any nation's PTO with only a single inventor. This is, in part, a matter of the nature of LED inventions: they require work on very expensive machines and they tend to build directly on work done prior to them. In my dissertation I discuss the creation of new knowledge in the Company's R&D department as a matter of working within a machine-material system. Any change you make within one layer of an LED chip (think of a layer “cake”) will, at the very least also have a direct impact on the physical connection, the electrical flow, and the flow of produced light between that layer and the layer it is grown upon. It will also affect the layer that will be grown on it. It may further affect the kinds of processes that can or now cannot be done many steps later in the production process (the new layer, may for instance, be more sensitive to temperature therefore forcing the engineers to turn up the pressure and down the temperature for a later, seemingly unrelated stage). All of this is to say that any particular new idea that gets implemented within an LED structure will involve input from a large number of people in charge of other portions of the production of that product. At least some of these will inevitably involve changes to the “invention” itself that will find their way into the patent's specification or claims. The complicated manufacturing techniques involved in LEDs (as well as in other semiconductor products) means that more people need to be consulted. The expensive nature of their production means that innovation in this field is extremely unlikely to come outside of a company or large research group-style academic lab. Nakamura's own early work on LED blue (and the surprise it gave to the industry) is the exception that proves the rule. Taking this a step beyond my own research, has there been an overall increase in the proportion of patents that come from this type of industry within the overall patent archive? Given the importance of semiconductor technologies and pharmaceuticals, at least, I would guess that their rise as complicated, high capital industries would account for some of the shift toward multiple patenting. I also would guess that, at least beyond the early Nakamura style work, the proportion of these industries' patents that have had multiple patents will have stayed relatively high.

A second place to look for why it is that multiple inventor patents have been increasing is the importance of the stage that an industry is in. Early on in a product's lifecycle improvements may be rather large and, perhaps, relatively easy to come by given the application of significant resources. In LEDs, early improvements would raise the efficacy of the products by huge percentages. By the time of Taiwan's early LED industry (which began in the 1970s, a decade or so after its beginning in the US and Russia), improvements were rather more modest in scale, perhaps on the order of 20-50 percent improvement at a time. By the time I arrived in the Company, they were starting to value improvements that gave maybe only a 3-4 percent improvement in efficacy; these were improvements that only a few years earlier would not have been thought of in terms of patents (or perhaps not even noticed) until they added up to around 10 percent.

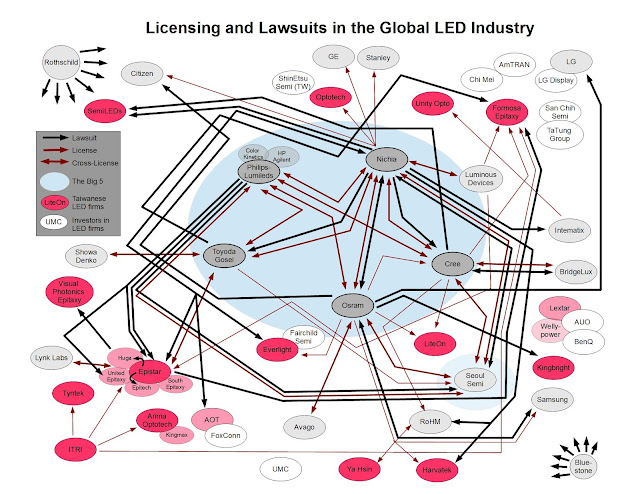

It is not that innovation has slowed in the industry, however. The problem is exactly that there has been so much product innovation that meaningful competitive differences between products may now be quite small in percentage terms. In the beginning, when there were tremendous percentage increases in brightness, this was due to the fact that early LEDs were so dim. Now, there are considerably more patents in the LED industry each year than there were before. More and more companies seek to protect themselves from proliferating lawsuits with defensive portfolios while also searching for anything that might give them an advantage in terms of negotiating a cross-licensing deal with any of the LED industry's Big 5. As a result, companies increasingly need patents and their need for patents goes above, beyond and is separate from their need for product innovation.

However, in order to get a patent issued in the United States, you must show a significant improvement over the patents already in the USPTO archive. To do this consistently, and to avoid spending money on a patent application they might later have to abandon, the Company's patent engineers might combine several internal invention ideas into a single application. In terms of patent law, this means that the creation of the patent's “single invention” now happens within the IP department much more than it does in R&D. As a direct result of the merging of multiple related (at least in the terms of patents if not in the terms of the lab) ideas into a single invention, these patents will always have more than one inventor. I suggest that this experience with “merging” is not something unique to the Company, but rather something that makes sense due to the rules of the USPTO (and other national PTOs) and the particular competitive situation of the LED industry. These same structural conditions are not difficult to then find in other industries as well. Returning to the original question of the number of multiple inventor patents, remember that this is a measure, not of the number of multiple inventor ideas in the lab, but of the number of multiple inventor patents that issue. If early patents in an industry tend to have single inventors and later ones multiple inventors, then the fact that more mature industries have much more patenting activity overall means that the overall numbers will tend to be skewed toward multiple inventor patents as the proportion of relatively mature industries rises within the overall set of patenting industries. As you get more patents (which we have), in many cases you will also get even more multiple inventor patents.

Finally, the overall increase in multiple inventor patents might also be explained by a relatively steady increase in the emphasis the USPTO gives to inventorship. A couple of comments on the original post (including one by Patent_Guru) point out how important it is for companies (or other applicants) to get the exact inventors “right.” The IP engineers in the Company had a responsibility to the Company to ensure that anyone listed on the patent was an actual inventor and that every inventor, no matter their rank, was actually listed on the patent. Mislabeling (ie. misrepresenting) either way could result in a powerful patent being invalidated at a future infringement trial or a potentially dangerous witness's testimony. While there were therefore many different sized contributions to a patent, all of the names were partial inventors and no one could be added just because they built the original platform or were the inventors' boss. If there has been a growing emphasis on precision in inventorship, this might also partially explain the increase in multiple inventors.

The increase, I suggest, is therefore less attributable to an overall change in global (or even American culture) and more to, first, a change in the predominance of a different type of industries and, second, to a difference in patenting trends for early as opposed to more mature industries. A the third, overall shift in emphasis within US patent law and court decisions may also have played a role in companies listing anyone who might have contributed just to be safe (perhaps less dramatic than the shift in US patenting style towards listing more and more references). What I find particularly interesting, however, is not the increase in multiple inventors or decrease in single inventors, but the fact that double inventor inventions have stayed steady. Is this a matter of the graph being expressed in percentages rather than absolute numbers? Is “unchanging” or rather “changing equally up as down” (ie. What might have been listed with a single inventor in the past now has triple inventors or more, but a replacement number of what would have been listed as single inventor patents in the past are now listed as double)?